I have written on numerous occasions, even fashioned an entire article, on the necessity for park historians to bring the voice of the general public to the forefront of park history. Giving voice to the people for whom the parks were created or to those who were directly affected by the park creation is not easy. Why? Sources are difficult to come by, and lack of sources can be a difficult hurdle to climb, particularly whilst trying to complete a dissertation. Nonetheless, I continue to steadfastly carry the torch for this historiographical cause…

Imagine my delight when I stumbled upon an exceedingly rich source in the Provincial Archives of Alberta today: the results of a public survey from 1974, asking the residents of Southern Alberta (and elsewhere) what they wanted from the proposed Fish Creek Provincial Park in Calgary.

Fish Creek Provincial Park, established in 1975, was part of the early 1970s near-urban park movement that swept across Canada and at its inception became the largest urban park in Canada, surpassing Vancouver’s Stanley Park in size. The first ‘near-urban’ provincial park to be created was Ontario’s Bronte Creek, located between Toronto and Hamilton, in 1971. I wrote a piece for The Otter about Bronte Creek last year. One of the driving factors fueling the near-urban park movement was the desire to further democratize access to outdoor recreation. Accessibility was the key buzzword.

Because of this spirit of democratization, provincial governments turned to the public for their opinions on park creation more than they ever had in the past. Surveys, like the one I found today, were a result of this desire to involve communities in the process of emparkment. The 1974 Fish Creek survey, created by the Fish Creek Provincial Park Planning Committee, consisted of a series of questions with boxes to check and an area to write-in your own opinion on the park or make suggestions.

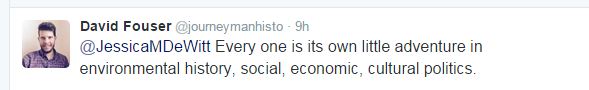

It is in these write-in answers that I found one of the most exciting discoveries of my dissertation process. As David Fouser expressed on Twitter, “Every one is its own little adventure in environmental history, social, economic, cultural politics.” Around 25,000 people filled out the survey, a figure that far exceeded the Planning Committee’s expectations. It is clear that the files I found only include a fraction of the responses given to the survey. However, the files do include those responses that the Planning Committee found worthy of note, which is significant in and of itself.

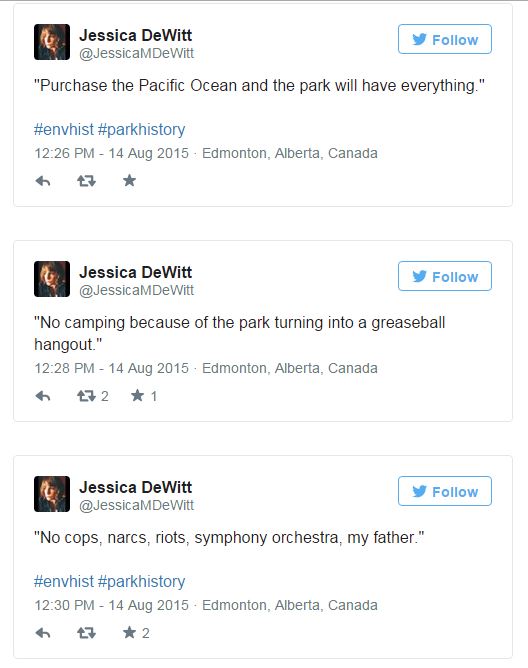

Many of the responses paint a humorous portrait of the public’s attitude towards the proposed park, but they also highlight important and serious issues, particularly classism, which is ironic for a project based largely on the goal of democratizing outdoor recreation access. One 5th grade survey participant got it: “the park should be fee because theres people who are poor and don’t have any money they can’t go to it,” he or she writes. Loathing and disdain for ‘hippies’ is strong. “Nothing for hippies – we already bought them a mall,” states one individual. As Ben Bradley has shown in his recent research, the 1970s marked a significant uptake in efforts to control unruly behaviour in parks, including drinking and partying, concern for which can be seen in the survey responses as well. There is a strong insinuation of who the parks are for and what behaviour is acceptable.

Many other social, economic, political undercurrents run throughout the responses. I’ll let them speak for themselves. I have provided a Storify of most of the comments that I found. They really are a treat.

The survey results can be found at the Provincial Archives of Alberta; W.G. Milne Fonds, ACC: PR2008.0411, Box 9.

Reblogged this on dexxxrated.

LikeLike